The Interior of Olveston

Orientation of the House

There has been much speculation that the siting of the house results from the thinking of a northern hemisphere architect but in fact, there is evidence to support the idea that the nature of the site and the climatic patterns were carefully taken into account.

Central Heating

The intention was that central heating would supplement but not replace the open fireplaces which were firmly associated in the English household at the turn of the century with ‘comfort’ and with concepts of family happiness and closeness. Originally, the heating system was solid fuel-fired. Diesel oil was later used and today, Olveston uses an electrically powered boiler and largely off-peak energy feeding the two huge storage tanks of its water-circulating system.

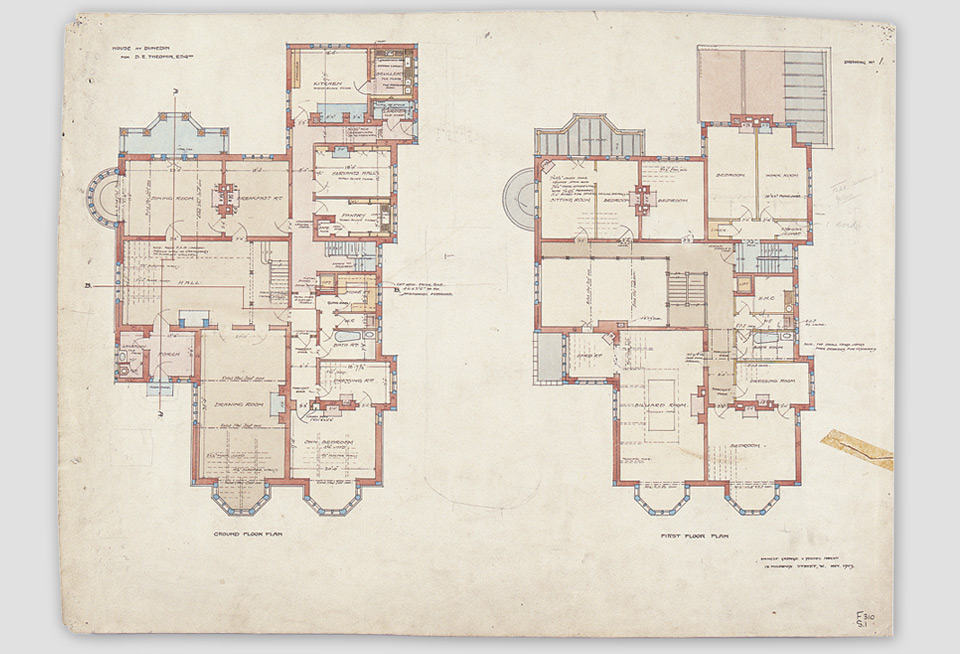

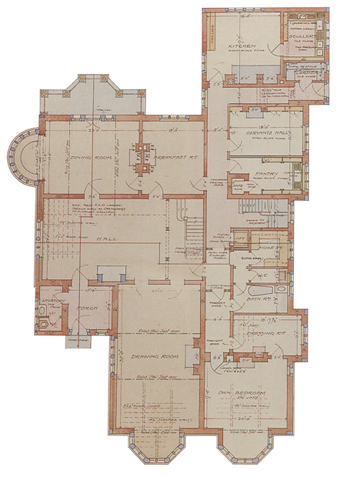

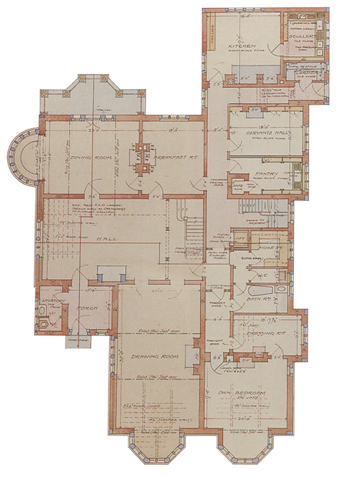

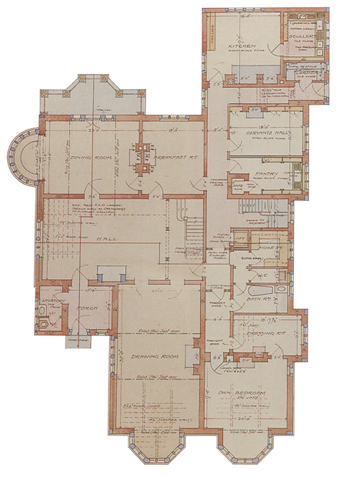

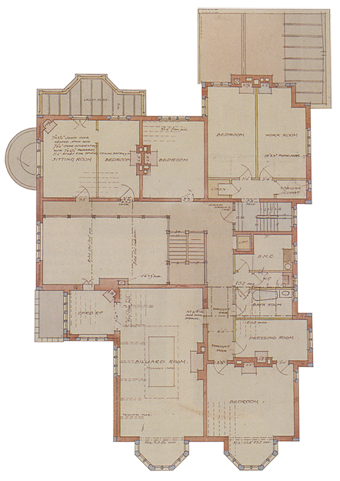

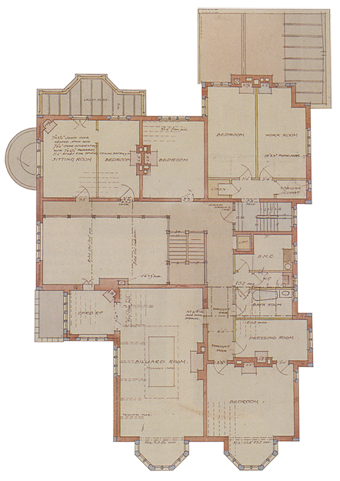

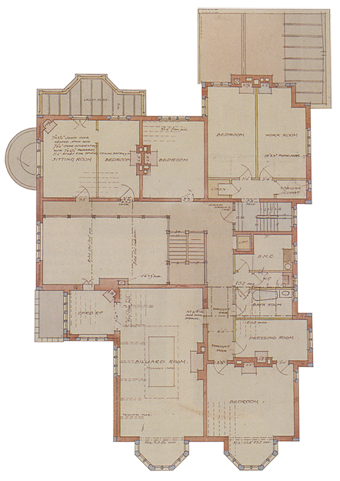

Above

Original plans of the ground floor and first floor

by Ernest George and Yeates Abbott, November 1903

Click through above to see

more of the house interior

The Interior of Olveston

The Reception Floor

Olveston conveys an impression of grandeur with its main entrance at the base of the tower, with its arms display in the vestibule and with its elegantly tiled cloakroom especially for the comfort of guests. The sense of grandeur is tempered by the comfortable proportions of the rooms and the linking of the library, dining room and drawing room with the hall to provide contrasts in size and decoration and an easy progression from one space into another. The Jacobean house of the seventeenth century was altogether more theatrical by comparison and its emphasis was on display and the confirmation of power and position rather than of comfort.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Great Hall

This was the centre for receptions and for meeting the entertainment requirements of the young adults in the family. It probably had its hey-day in the earlier years but it remained inevitably a focal part of the house. The oak joinery was the work of Messrs Green and Abbott of London. There are indications that this firm contributed to the provision of other furnishings for the Theomins. The wall covering is the original printed hessian made by the firm of Turnbull and Stockdale of Lancashire which had a London showroom in Regent Street. The head designer for this firm was the famous Lewis Foreman Day who specialised in fabrics and wallpapers and wrote many books on design. The pattern on the hessian in Olveston’s hall is based on a renaissance velvet featuring acanthus leaves.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Drawing Room

In the evolution of the English manor house out of the mediaeval castle, the drawing room has a fascinating origin. In earliest times, the great hall where everyone gathered, developed a raised dais at one end and there, at meal times, the family and the intimate or influential guests sat at a ‘high table’. A separation from the hurly-burly of servants, retainers, lesser guests and hangers-on was by this means implied. The next stage of development came when the family in search of both privacy and comfort ‘withdrew’ from the hall. The dais then became closed off to form the ‘withdrawing room’. Over the centuries, the basic purpose of the ‘withdrawing room’ changed from being a private eating room to being a place for the family to receive special guests.

The drawing room at Olveston reflects this evolution and focuses on the Victorian and Edwardian purposes for the room, - a place for music and the receiving of visitors, especially by the lady of the house presiding over afternoon tea. It also became a place for the display and enjoyment of the furnishings of every variety which for the late Victorian people of means, equated with comfort. In the present time, such a room faithfully maintained can, without a lot of explanation, speak to the visitor about the tastes and interests that its family favoured.

Olveston’s drawing room has the only decorated ceiling in the house. The wallpaper is light and is a re-creation of the original which was a Birge and Sons Company product from Buffalo in New York State. It is ideally suited for displaying the watercolours that dominate the walls. Stained glass windows by Bryans and Webb of London pay tribute to the arts. Details of the decoration in these windows are appended to this paper.

The late nineteenth century upholstery fabric is based on the French silk brocades of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The brass curtain rods are simple and they replace the elaborate and heavy canopies of the preceding periods in the history of Victorian domestic fashion. You should note that the antimacassars of earlier time, unlike the heavy drapes, have not been discarded on the furniture.

Note the focus on the fireplace, reinforcing the Victorian ideal of home comfort. The collections including the furniture are eclectic. There is no conscious effort to pursue a style or to follow a fashion. This room deliberately contrasts with the darker colour schemes in the dining room and the library on the other side of the hall.

The Interior of Olveston

The Dining Room

Light and shadow play a brilliant duet with the aid of the splendid half-circular window and the generous windows and doors opening on the loggia with its view on to the trees. Again, the fireplace dominates one end though it melds more into the general scheme of the room than is the case in the drawing room. Lighting is muted. The centre light can be raised or lowered. Silk shades soften the impact of the light globes. The rich wallpaper looking like embossed leather, is original both here and in the library. It is another product of M.H.Birge and Sons Company.

There is a greater discipline in the dining room furniture than is the case in the drawing room. The plain elegance of the main table is reinforced with the impressive simplicity of the pair of sideboards dating back to the time of the Napoleonic Wars,(1805-15). They represent the final refinement of a complex piece of furniture that had evolved through several forms during the eighteenth century. Unlike the sideboard in the dining room suite of today, their storage function was only minimal. In mediaeval times, the board was the table, thus the sideboard became the side table upon which the food was finally dressed for presentation at the main table.

In contrast with the plain lines of the sideboards and the dining table, the carved Chippendale-style chairs with their relatively high backs add a decorative flourish without overstatement. You should note that oil paintings hold sway in the dining room complementing the rich character of the furnishings.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Library

An intimate room where the play of light and shade is again appealing. Warmth is reinforced by the use of oak panelling together with the richness of the wallpaper. It should be noted that the curtains are not original. The green carpets in the library and the dining room follow the Edwardian enjoyment of this colour. There is a Chinese flavour to their patterns but their structure is not in the character of Chinese carpets. Their exact source has never been confirmed. Early drawings from Ernest George and Yeates indicate that the library was first designed as a breakfast room, but presumably the wishes of the Theomin family were respected when it was furnished as the library. Its position between the dining room and the kitchen seems a little strange until this change of function is understood.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Kitchen and Services areas

on Ground Floor

It is perhaps in this area that the evidence of Ernest George’s attention to the wishes of his clients is best seen.The kitchen and scullery are of ample size for a number of servants to work effectively. Each room has good windows and ventilation. The double copper and also porcelain sinks in the scullery address some of the specific requirements of people who followed the Jewish laws. Hatches linking the scullery, the butler’s pantry and what was once the servants’ dining room, minimised pressure in the long passageway leading to the family rooms. These hatches formed one of three service links at Olveston. The other two links were the network of internal telephones on all floors allowing the family and the staff to talk to each other, and the elaborate bell call system centred upon the passage wall outside the kitchen door.

These conveniences and others such as the manual counterweighted service lift connecting all four levels and the magnificent solid fuel Eagle range, remind us that Mr Theomin intended his house to be not only a show place and a comfortable home more akin to Victorian tradition, but also an up-to-date Edwardian dwelling with all modern conveniences. At the very beginning, electric light was provided by a gas engine firing a generator in the basement but it was not long after the house was inhabited that electricity was laid on.

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Ground / Reception Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The First Floor

The fine staircase leads to a gallery on to which the private family rooms open. On the whole, room proportions are modest though adequate reminding us again that Olveston was first and foremost a home for the comfort and convenience of its family. When we commenced the long task of redevelopment in the first floor rooms, we were constantly taken by surprise with the discoveries made when the walls were stripped back. Textbook propositions as to how typical rooms in the typical house of the character of Olveston were decorated in their time, had to be jettisoned and the results which you show to the visitors were dictated by the discoveries we made. It was as though the Theomin family were stating all over again what they wanted in the rooms that were personal to them.

By the time Olveston was being designed, fresh air had become fashionable. Sunshine and good hygiene received more attention from architects and designers and the windows in all the Olveston bedrooms reflect this contemporary concern. It is noticeable that there is no room that lacks an appealing view of the outside world, whether it is a small corner of the garden or a panorama over the harbour, the beaches or the open ocean. Visitors do not see the former servants’ quarters but it is noteworthy that the hierarchy of servants was preserved at Olveston through the provision made for them. The rooms intended for the senior staff could be distinguished by their dimensions and their placement in the plan of the house.

The First Floor

The First Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Billiards Room

A room of fine proportions to accommodate the largest sized table - 12ft 6ins by 6ft 3ins. Steel girders beneath the floorboards support all the table legs to take the weight of about two and a half tons. The height of the lights can be adjusted by one rope and by another the overhead louvres could be opened for ventilation. Seating on a raised platform followed tradition and provided a convenient viewing point for non-players.

The First Floor

The First Floor

The Interior of Olveston

The Card Room

This is the original name for the small room opening off the billiard room which has been known by many names during its history. An exotic corner with its own small fireplace, it served several functions, first as a card or games room. It was a comfortable little lounge for those not interested in the activities of the billiard room. With the opening of the “Juliet” window, looking down on the hall, it forged a link between the upper floor and the reception area when extended entertaining was in progress.

The First Floor

The First Floor

The Exterior of Olveston

The Garden and Conservatory

The house is set on an acre of garden surrounded by beautiful mature trees, many of which are specifically nominated as protected specimens under the city’s district plan.

The formal garden is structured around original terraces, paths and flowing lawns. The garden features a large conservatory that has been recently restored based upon the original plans of 1904. The heated conservatory features a display of plants all year round.

The individual spaces that make up the garden include many original plantings of fine rhododendrons and native plants. There are a number of seats around the grounds to allow visitors some rest and relaxation while taking in the special vistas that the garden provides.

The garden is tended all year round and provides the visitor with another interesting dimension of the life lived at Olveston. A visit would not be complete without a walk around the gardens.

The Exterior of Olveston

1921 Fiat 510 Tourer

In 1922 Mr Theomin took delivery of a brand new Fiat 510 Tourer. This limousine was a classic example of elegant European motoring. 3.4 litres of driving pleasure, the car was used by the Theomins for many journeys into Central Otago and up the east coast of the South Island.

Some 72 years after it was purchased, the original Fiat was discovered, standing axle deep in water, in a derelict farm shed a short distance from Dunedin. The vehicle had not moved for over 33 years.

In 1994 it was transported to Christchurch, New Zealand and fully restored by Auto Restorations Ltd. The work took over 2 years. The Fiat was returned to Olveston in 1996 and is now maintained in tip-top running order.

It has pride of place in the garage that was built in 1914. The garage incorporated a heating system, a pit for servicing and a carport at the rear for the chauffeur to clean and load the car for any long journeys.