Olveston c.1906. View from Cobden Street.

Olveston c.1906. View from Cobden Street.

When Mr and Mrs Theomin set off on an extensive trip to America, Europe and the Far East in 1902, they were much taken up with the objective of building a fine home for themselves in Dunedin. In their search for an architect, they first looked at the work of a Canadian before they settled upon Sir Ernest George in the London partnership of Ernest George and Yeates.

While in London in 1903, the Theomins obtained working drawings from Sir Ernest George for a Jacobean-style mansion. Sir George’s name is associated with Philip Webb and Norman Shaw among others, who greatly influenced the course of international modern domestic architecture.

Olveston was constructed between 1904-1906 by Robert Miekle, with Mason and Wales supervising the project.

Built with every modern convenience, Olveston was fitted with central heating, a gas generator for electricity, a shower in each bathroom and heated towel rails, an internal telephone system and service lift.

The house had 35 rooms (including a vestibule, hall, drawing room, bedrooms, billiard room, card room (or Persian room), kitchen, scullery, butler’s pantry, library and dining room) with a total floor area of 1276m2. A galleried atrium through the ground and upper floors forms the Great Hall, which served as a ballroom.

The London firm of Green & Abbott were responsible for much of the interior design, including the English oak joinery. The original wallpapers were manufactured in Buffalo, New York and selected by the Theomins on one of their trips to America.

The exterior walls of Olveston are constructed of brick and plaster with a Moeraki gravel finish and faced with Oamaru stone, finished with Marseilles roof tiles.

British architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner visited Olveston in 1958 and described it as ‘an extremely interesting and very grand house’.

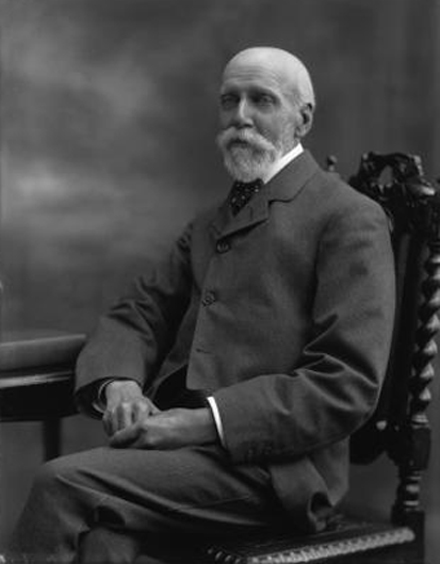

Sir Ernest George (Architect)

Ernest George, trained in the office of Samuel Hewitt and at the Royal Academy Schools. In 1859, he won a gold medal for architecture.

He set up practice in London with Thomas Vaughan in 1861. Quite soon, his real talents were revealed in the field of domestic architecture. He took offices in Maddox Street, off Regent Street, and from 1871 to 1893, operated successfully in partnership with Harold Peto. When Peto retired, George was joined by Alfred Yeates and it was during the course of this partnership that Olveston was designed.

Apart from his reputation as an architect, Ernest George also published books of etchings and lithographs of Venice, Belgium and the Loire. In 1911, he was knighted.

Olveston belongs in the mature period of Ernest George’s working life. It is his only known house in the Southern Hemisphere. George was not a brilliant architect but he was skilled in drawing on the substantial traditions of English domestic architecture from the time of the Tudor monarchs through to the end of the Stuart era. That double century saw the steady evolution of the English house from the fortress to the fortified manor, then to stately country mansion and gradually to comfortable if often sprawling country home with the last vestiges of a strategic stronghold cast aside.

In the later part of the nineteenth century, the excesses of Victorian Gothic architecture were quelled in various ways. There was a significant revival of interest, albeit romantic, in the great traditions of English house building of the Tudor-Renaissance, Elizabethan and Jacobean times, seasoned with the influences of the English Arts and Crafts movement and the novel manifestations of L’Art Nouveau, blowing in from France, Germany, the Lowlands and Spain.

By the time Olveston was taking shape on the drawing boards, Ernest George was adopting a disciplined approach to the main features of the Jacobean, when compared with the more exuberant houses he had been designing in the 1880’s. Ernest George’s practice involved much remodeling and restoration work and this, together with his mild manner made him amenable to the wishes of his clients. Thus, while continuing to be influenced by the wealth of decorative detail provided by the elaborate ceilings, the rich carving of staircases and wainscoting ornamenting the old houses that captured his fascination, he was by 1900 observing a strictness of form and a sensitivity for fine detail more suited to the design of houses on a more moderate scale.

You may find it helpful to seek out and explore illustrations of houses in England that influenced Ernest George in designing houses like Olveston. Their origins spread from early in the reign of Henry VIII to the middle of the reign of Charles I: Barrington Court, Somerset, 1514; Montacute House, Somerset, 1518-1600; Burton Agnes, Yorkshire, 1589-1603; Blickling Hall, Norfolk, 1620; North Mymms Park, Hertfordshire, 1600. George designed a second wing for North Mymms during his partnership with Harold Peto.

Sir Ernest George (1839-1922)

Sir Ernest George (1839-1922)

You will find a reference book on the life of Sir Ernest George and his architectural contributions, put together from a miscellany of documents in the staff room reference library.

At the turn of the century, a range of customs and conventions lay behind the planning of English houses in the character represented by George’s work. Olveston maintained these conventions and transferred them twelve thousand miles to the other side of the world. Such houses were designed to provide a pattern of living for a fairly fixed domestic routine meeting the needs of an adult family and their resident servants. The division between the family and the guests on the one hand and the servants on the other, remained quite marked in the house structure, even though the daily functions at the colonial end of the axis seemed often to blur the division.

The new upper middle class wealth led to the adoption of a style reflecting that of the old landed families in England. There were modifications in the homeland and even more modifications in the colonies. For the newly wealthy, the desire for a house in the country was not the same as the desire to posses the traditional country house with its complex estates and the trappings of political and social power. The drawback in the minds of the new clients was the responsibility that went with the privileges implied in the great landed estates. The newer houses in the country were for entertaining, for indulging in ‘the arts’ and for providing the setting that allowed free rein for collectors' passions. In an age of relatively cheap labour and fuel, the Victorian perceptions of comfort could be well catered for. New technology brought increased convenience, - better telephone and electric telegraph, and a succession of labour-saving inventions that were to the advantage of home management.

Find out more about the construction

Find out more about the construction